GERD and the Nile Dispute - Navigating Law, Power, and Survival

- Sambhavi Sarma

- Jul 8

- 5 min read

1. A Dam for Progress, A River of Tensions

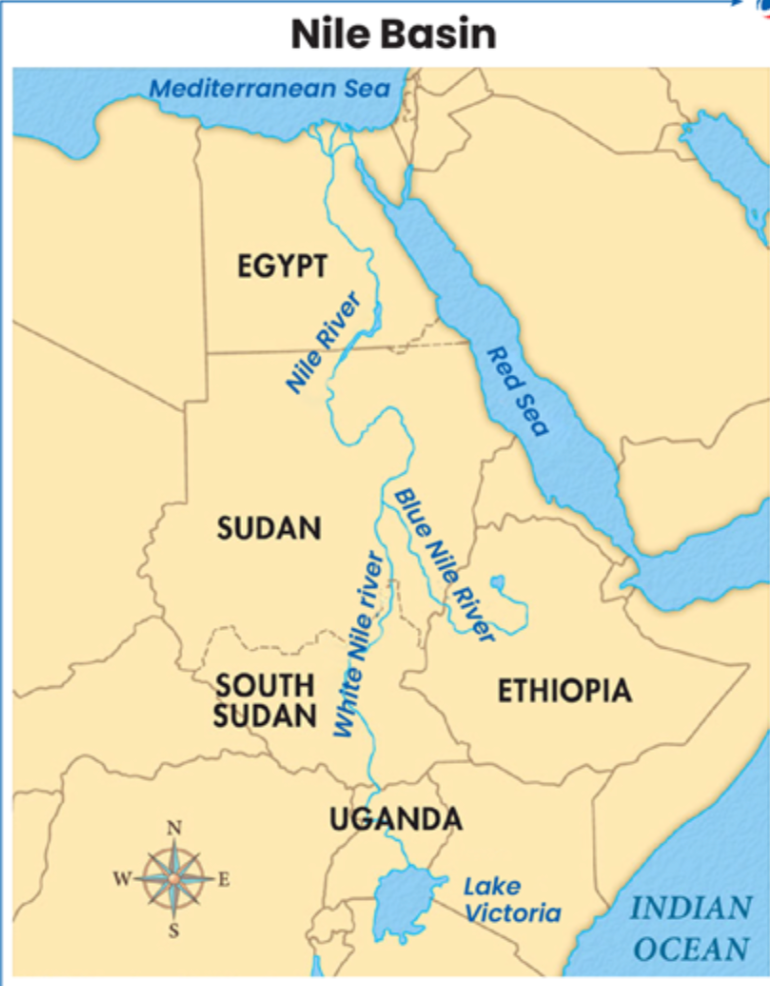

As the dynamic geopolitics pose a challenge for international law, GERD, the largest hydropower project in Africa, presents a complex situation in terms of sustainable and just use of resources. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) provides 5,150 megawatts of electricity to 65 million Ethiopians with first access to electricity. This was built with the view of helping Ethiopia become the energy hub among its neighboring countries while also being a self-sufficient source of electricity. However, this process does not remain short of challenges, as it raises concerns of irregular water flow and lack of food security in Egypt and Sudan.

2. Old Agreements, New Disputes

Ethiopia’s solution to meet its energy shortage was met by the concern of huge reservoirs to be maintained in the dam’s initial phases. Egypt and Sudan would be significantly impacted by the same as Sixty percent of Egypt’s water comes from the Blue Nile tributary originating from Ethiopia, whereas the majority of the seventy-three percent of Sudan’s annual freshwater that comes from the Nile River is from the Blue Nile. This dispute, though it may seem new, can be traced back to the colonial era. In 1929, a treaty was signed by Egypt and Great Britain (representing its colonies) where ultimate authority was given to Egypt—The “construction, maintenance, and administration of the works shall be under the direct control of the Egyptian Government”. This treaty was a disaster waiting to happen, as it paid almost little heed to the interests of Sudan and none to Ethiopia’s. In the following Nile Treaty in 1959, Egypt and Sudan agreed to share the waters between themselves in a quota of 55.5 BCM to Egypt and 18.5 BCM to Sudan, leaving only 10 BCM that evaporates from the Aswan Dam. This agreement between the two countries was reached without due consideration to the rights of the other upstream Nile countries. Thus, even though Sudan and Egypt adhered to this treaty, enforcing the treaty became almost impossible as Ethiopia refused to comply due to lack of interest. Ethiopia continued to reject the colonial treaties and cited the 1997 UN Waterworks Convention. Ethiopia, with respect to the Harmon Doctrine (which implies Ethiopia’s authority to utilize the resources in its sovereign territory) and the convention, which reiterates that emphasis was placed on “just and equitable use of resources,” creates a convincing case for Ethiopia to demand its rights to the Nile. Egypt and Sudan continue to state that there was emphasis placed on the obligation to not cause significant harm to another. Both the countries seem to be correct, as the treaty is subject to interpretation and does not lead the conflict anywhere.

3. Talking Tables: Cooperation, Commitments, and Cracks

An initiative by Ethiopia followed in which there was the appointment of the International Panel of Experts (IPoE) in 2013 with the consent of all the countries. This panel analyzed the complications and implications of the project and came to the conclusion that there was “an absence of significant harm the dam would cause to other downstream countries and the many potential benefits of the dam to Sudan and Egypt”. After this panel’s findings, Sudan observed the potential benefits of the dam and became more open-minded to the construction of it. However, Egypt still continued to oppose the building of GERD, whereas Ethiopia used the panel’s findings as a strategic weapon to build the dam. Another effort to cooperate was made in 2015, where the countries signed the Declaration of Principles on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Project (DOP). Egypt signed this treaty as it realized that it had to finally partake in a realistic agreement. This treaty established that Ethiopia had the right to build the dam, but it had to be cautious not to hamper or restrict the flow of resources to Egypt or Sudan. However, this proved to be a blunder, as Ethiopia falsely claimed that it was adhering to the agreement, and due to the non-legally binding nature of the agreement, it demanded for the issue to be sorted without the intervention of the UNSC. This helped Ethiopia’s case, as there was a gray area for it to function in. The latest efforts to mediate this conflict came from the US along with the World Bank in November 2019. Several rounds of these talks took place in the capitals of these respective cities, where it was established that a new agreement would come into place; however, soon enough, Ethiopia skipped the scheduled meetings in Washington, DC (security context). Through these meetings, the US concluded that the Nile is an African issue that should be solved by Africans and further encouraged the African Union to lead the countries to a mutual agreement. However, the US-led mediation still remains the latest development towards a mutual agreement in this conflict. There continues to be a lack of one agreement that all the countries agree on; this creates a legal deadlock and prevents any possible developments.

4. Finding the Flow Forward: Suggestions for Lasting Peace

The conflict surrounding the building of GERD is unlike any other. It involves complex issues such as the varied interpretations of law and uncertainty regarding the resources, which is further escalated by climate change. It is essential that effective and logical solutions are drawn to push this conflict out of the existing deadlock into a more receptive area. The first and foremost step to ensure a push to cooperation would be to form a permanent monitoring committee involving representatives from all three countries along with representatives from the UN. This will help the countries to create a mechanism of self-reliant solutions without the complication of external parties. This committee can examine the rains and climate change and administer the building of such structures near the Nile. The permanent nature of the committee would ensure that peace and coordination are maintained in the long run while also providing a strong platform with mediators for discussion. The following step would be to ensure that Ethiopia agrees to a compensation or collateral mechanism if the building of the dam leads to significant loss to Egypt and Sudan. This compensation or collateral can be in resources or monetary form to ensure the safety of both countries in cases of emergency. Although the aforementioned suggestions may not be refined solutions, they are an initial stage of a comprehensive and sustainable solution. Thus it is essential that these aspects are inculcated into the long-term plan for conflict resolution by the concerned countries.

5. A Shared River, A Shared Future

The Nile remains a source of livelihood for the majority of the African countries. Restriction or ban on the use of the resources in the area is equivalent to inviting destruction. Equitable and judicious use of resources is required to ensure that there is sustained growth and development of the countries. Any discrepancy among the three nations can create a hostile environment for other countries. The surging climate change and growing global uncertainty only complicate the existing challenges. Through coordinated and effective efforts, the Nile can unite people rather than dividing them with conflict.

References:

https://lawjournals.celnet.in/index.php/njrel/article/view/1719

https://natoassociation.ca/the-ethiopian-dam-and-its-impact-on-egypt-and-sudan/

https://thearabweekly.com/ethiopias-gerd-breach-international-law

https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1232&context=jelr

https://www.aimspress.com/aimspress-data/aimsgeo/2022/2/PDF/geosci-08-02-014.pdf

https://www.ide.go.jp/library/Japanese/Publish/Reports/AjikenPolicyBrief/pdf/173.pdf

Comments